Island hopping through the West Bank with Mazin Qumseyah, Si discovers the power of place names and who’s got their hand on the tap.

“How can you tell the difference between a Palestinian and an Israeli house?” asks Mazin.

“Er, sorry?”

“Come on, how can you tell the difference between a Palestinian and an Israeli house?”

It’s 7am and I’m driving to Nablus with Mazin Qumseyah, a wily Palestinian Doctor of Biology who gave up an associate professorship at Yale University to return to the country of his birth. It’s early for guessing games.

“Okay,” I say. “I’ve got it. The Israeli houses are built in anally regimental lines and are surrounded by razor wire and… the Palestinian houses are falling down?”

“Look at the roofs,” he says. “Palestinian houses have water tanks on the roofs.” He’s right. Twenty years ago you turned on a tap in Ramallah and water came out, now you’re lucky if you get it twice a week. So Palestinians save it up. We chuckle, then Mazin says: “During the last uprising, Israeli soldiers would come and shoot the water tanks. Just out of spite.”

We bump and lurch down the snaking, chewed up, single lane into the Wadi Qelt – the Valley of Fire (or Death depending on who’s translating) – a thick rolling scar that cuts the West Bank from Jerusalem to Jericho. This is the only road Palestinians can use to get from the south to the north of the West Bank.

Today the Wadi does not smell good with untreated sewage running down from the settlements and the villages. “We have the money, millions of dollars in aid donations, to build a water treatment plant here to deal with it,” ays Mazin. “But Israel won’t allow it.”

Water, it would appear, is the imperialist’s gold standard choke chain and, in a land as parched as this one, it is particularly effective. Gaza’s water treatment plant was one of the first things Israel bombed during the siege. The twisted and twisting separation wall has parted the West Bank from over three dozen aquifers that produce six million litres of water a year. Meanwhile Israel and its settlers guzzle something like 80 per cent of Palestine’s water.

Two days later I’m in bar in a Bethlehem suburb struggling to be understood.

“You want a half?”

“No,” I say. I do hand signals. “A big one.”

“Yes,” says the barmaid. “A half.” It turns out it’s not a language thing but a metric thing.

At the back of the bar I find Saleh Al Rabi, an engineer from the Palestinian Water Training institute, nursing a bottle of Tayber. I mention the soldiers shooting the water tanks.

“They say there’s no Palestine without the Al Aqsa,” he quips. “But there’s no Palestine without water.”

I remind him about the Palestinian writer Marwan Bishara who said ‘the map of the settlements looks like a hydraulic map of the territories’. He’s heard it all before.

“Even Ariel Sharon said, ‘The settlements are where they are for a reason’,” he says.

Saleh tells me how Israel plans to build two desalination plants on its Mediterranean coast and pump the water into the West Bank. “That way they can turn it on and off at will,” he says. “Many Palestinians are already paying around a third of their income on water. We pay four times as much as the settlers who have 24hr water and swimming pools.

“The situation in Gaza is even worse,” rails Saleh. “Israel drains all the gravity feeds running down from the Hebron hills into the Strip. On top of that, the Gaza aquifer is, possibly irreversibly, polluted with seawater. They say the water is so polluted in Gaza, that if a Gazan drank bottled water he’d get sick.”

In Mazin’s car we count checkpoints and play a game trying to match the Palestinian villages we pass with names on our map because the road signs only point out the settlements.

Dr M’s lifelong friend and associate Aziz , a columnist for Al Quds newspaper, riding with us to Nablus, can’t get his head round my name. I tell him it again, two more times. He shakes his head. “I will call you Salim,” he says.

“Okay,” I say.

“Salim, you know the Arabic wording on the signs [given after the Hebrew and the English] isn’t even the Palestinian name for the town or the village but just phonic translations of the Hebrew.” Later, we will pass the left turn for the bustling Palestinian city of Salfit. The sign just says ‘Tel Aviv’.

The sensible route to Nablus wouldn’t be this way at all. It would be through suburban Jerusalem, it would take 40 minutes tops. But there’s a 10m wall in the way and Dr M’s Palestine plates mean he’s not allowed to drive the sterile highways that connect the settlements to Israel. This is the only way through. Trucks, buses, collapsing Cavaliers all have to arge and barge along this crumbling road.

“We call that one the Lieberman Highway,” says Mazin as we pass under the shiny new blacktop that runs from Nokdim – home to Israeli Foreign Minister Avi Lieberman – with Jerusalem. “It’s a settler road. Not for Palestinians.”

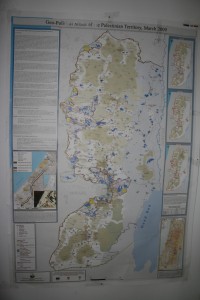

In Aza’in the road turns to grit. Aza’in, you see, is security zone B. At a glance, the geopolitical map of the West Bank looks something like Scotland’s Western Isles. But take a closer look, and you can see just how calculated the fragmentation of Palestine is.

The brown sections (less than 10 per cent of the total) are under Palestinian Authority control. Here the PA can dish out

building permits and the Palestinian police can strut around with AK47s making sure people wear seat belts. The dark brown sections, like Aza’in are Zone B – here, the Israelis have also thought to unburden themselves of the day to day organisation of Palestinian society but, due to the ongoing ‘security threat’, the Palestinians are not allowed to have any civic authority of their own. So there isn’t one and the road stays trashed and the rubbish uncollected.

Zones A and B float in the direct military control Zone C. This includes all the settlements (in blue) and the land connecting them. The Jews-only roads make it even harder for Palestinians to get about, and the dirt tracks that connect Palestinian villages barely register on the map. The East and West Security Zones – running up to 20 klix into the West Bank from the Israeli and Jordanian borders are loaded with army bases and settlements ranging from full on towns to a gang of armed zealots in a cluster of caravans. Palestine is an island nation.

Human rights groups have began calling these fragmented enclaves Bantustans – it’s the name given to the black enclaves created by the Apartheid regime in South Africa 1947, the year of the birth of Israel. The analogy is not wasted.

“There is an international convention against Apartheid and Israel fulfils it all,” says Mazin, swerving round an oncoming taxi. “Israel has it’s own word ‘Hafrada’ – it means segregation, same as ‘Apartheid’.”

Jeff Halper from the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions compares the West Bank to a jail. On the surface it looks like the prisoners run the place – they, after all, make up most of the population, have the cells, the yard, the canteen. The jailers only control the keys, the doors, the walls, watchtowers, guns, punishments and the length of the sentences.

We drive past an elderly Bedouin woman herding scorched sheep from a muddle of corrugated pens. If you stood on the water trailer the Bedouins have had to drag into their camp to survive, you could probably see the date palms sprouting from the settlement of Adummin on the hill above. The Bedouins, nomads from the Jordan Valley, were ‘relocated’ here to these shacks. Now the Israelis want to move them on again. You’re never cured of being a refugee – you’re just in remission.

At the top of the hill we hit Route 60, the Jerusalem – Jericho road. Mazin describes it as “the backbone of the Israeli settlement structure”. It’s a fast moving carriageway that Palestinian drivers are allowed to share. The sharing turns out to be mostly nominal. ‘Welcome to Jabba’ reads a sign erected in ironic protest by the village’s residents above the fifty tons of rubble that blocks their access road. Further on, a similar scene greets us at the entrance to a village we think may be called As Sawiya. In the distance, the separation wall rises like a fin from the red earth, behind it white stone blocks stand rigidly to attention.

We pass a sign for Bet El.

“What happens there?” I ask.

“That’s home to the Israeli-run Palestinian Civil Authority,” says Mazin. “There’s nothing civil about it. Literally or metaphorically.” It’s where Israeli officers in civilian clothes control the West Bank.

Razor wire and watchtowers signal Israel’s largest West Bank military base. Rows of dreaded D9 bulldozers – six inch armour plated monsters built exclusively for Israel by the Caterpillar corporation with the explicit aim of flattening Palestinian homes – taunt us from behind caged grills.

On a hill near Ramallah we see the solitary fortress of one infamous US millionaire settler who stalks the surrounding hills with his M16 picking off Palestinian sheep. And by the turn for Eli, we pass a giant billboard of a smiling white child declaring ‘Welcome to Judea and Samaria It Belongs to Every Jew’. Several miles later we pass the turn for Eli Cemetary. I ask Mazin about this.

“They put the cemetery far from the settlement,” he laughs. “So they can colonise land even after they die.” No Israeli government however liberal – and believe me, they ain’t – is ever going to evict dead Jews. “That’s why talk of a two state solution is delusional,” says Dr M. “There’s a half a million settlers in the West Bank. Who is going to move them?”

As the climbing sun bleaches the colour from the day, we drive through the village of Hawara. Hawara reached notoriety in 1989 for what became known as the ‘night of the broken clubs’. It was during the first intifada that Israeli troops came to Hawara and made the mayor cough up twelve young men. The soldiers took them up into the hills and smashed the arms and legs of every man but one. The beating was said to take three hours – and the beating was so severe the clubs broke. They only smashed the last man’s arms, so he could walk back for help.

Hawara is also the location of the main checkpoint into Nablus. Today the checkpoint is quiet, new ‘relaxed’ measures mean we can drive into the city. A few weeks ago we’d have had to wait for hours before leaving our car at the checkpoint and walking in. “Don’t you go a bit crazy living like this?” I ask Mazin.

“We’re all crazy Salim,” he says as we pass two sneering, uniformed youths slouched over their M16s. “And the craziest people of all are running the show.”

Nablus is the closest I’ve got to a functioning Palestinian city. Aside from the checkpoint on the edge of town, the city appears to be free of petulant gangs of Israeli soldiers, sharp elbowed American God-botherers, settlers and sites of disputed theological importance (though later I learn Rachel’s Tomb is here – a grail for hardcore othordox Jews). As it happens the indigenous Jews of Nablus, the Samaritans, have lived harmoniously with local Muslims for millennia. In 1948 they turned down Israel’s offer of citizenship, though I’m told more young Samaritans are opting for a pass that’ll get them through the checkpoints these days.

Over mud-like Arabic coffee, my companions Aziz and Mazin tell me about the city’s strong defiant streak and how most families have lost someone in the struggle. On the road in, we passed a huge construction site where they are rebuilding the municipal buildings razed in an F16 air strike three years ago. “Collective punishment for daring to resist,” says Dr M.

We arrive at An Najah University. There is an event to mark the opening of the American Studies department and Mazin, who is a lecturer at Bethlehem and Birzeit University as well as the director of the Palestinian Centre for the Rapprochement Between People and a tireless human rights campaigner to boot, is due to speak.

The car park is blocked by a bunch of bullet-proof 4x4s – the US Consulate’s Cultural Affairs officer is in attendance too. With some difficulty we manage to get one of the neckless CIA goons moodily fingering their earpieces to shift a truck so we can park.

The inauguration starts badly. The keynote speaker, Dr Philip Hosey from New York University, gets up to tell assembled faculty and students how “America created the concept of the democratic faith” and “has the longest tradition of social equality in the world”. He suggests Palestinians should stop clinging to Islam and become spiritual “like Italian Americans” who get on swingingly with their Jewish neighbours. There’s no mention of the security council vetos or the £62billion the US has given Israel to enable them to persecute and slaughter Palestinians for two generations. He talks about US diversity and suffrage, “okay, so it only applied to white male property owners”, as the model to follow. I look along the row where I’m sitting to see ten pairs of white knuckles in tight clenched fists.

Outside I run into Amjad and a group of English language students from the Uni.

“What do you reckon to that?” I ask.

“It was…very interesting,” says Amjad, guarded with an eye on the G-man hovering nearby.

“Interesting? Are you mad,” I say. “That was bullshit. It was total fiction!” I apologise for my sloppy English, but my sentiments seem to relax the boys.

“They give us an American studies department and send in F16s,” jokes Ahmed.

We chat about the city and life and plans. Most of them want to graduate then go abroad to study for masters degrees.

Back in the hall another US apologist, Amanda Pilz, describes the colonisation of the West in terms that would possibly be welcomed the other side of the Hafrada wall (it was a wilderness till the Europeans got here). It seems beyond irony in this venue. As she speaks the US cultural affairs officer turns to her colleague and mouths, “She’s good”. But the truth is she’s a liar.

The American contingent seems to have spectacularly mis-pitched itself. Their patronising manner and language exposes their contempt for their audience. No one bothered to tell them that Palestinians, despite the occupation, have more graduate degrees per head of population than anywhere else in the world. With unemployment levels that’d make Moss Side look like Silicon Valley, education has become something of a fetish for Palestinians, and for those that can raise the money, they go on and on. Today I will meet more people with doctorate degrees in a single day than any other day of my life. During the afternoon session we will slope off so Aziz can buy a laptop off a mate of his. The computer seller, Iyad, who lives a tiny village in the hills north of Nablus. He has a masters degree. In the flat upstairs he introduces us to his father who’s walls a covered with the certificates earned by his children. All his sons have masters degrees and three of them have science based Phd’s and they sell laptops for a living. Pilz and Hosey, it seems, have bought the Israeli line about Palestinians being an itinerant, illiterate people.

Finally the Palestinian contingent get to speak and they do it in an articulate and sharp witted, non patronising, way in stark contrast to the Americans.

Dr M throws out his prepared address (he tells me later) and lays into Hosey’s “myths”. He tells students they should learn the truth about America, he shows them maps of Palestine before and after the Israeli occupation and maps of the US before and after “the largest genocide in human history”. He tells them about slavery and how the US has bankrolled Israel’s massacring of the Palestinians. He tells them to read Howard Zinn and Edward Said and that they shouldn’t waste their time trying to effect change from the Whitehouse but should talk directly to Americans on the internet citing the civil rights movement and Vietnam as examples of how people pressure in the US can make a difference. He passes a paper round. “Give me your email addresses,” he says. “I will help you.”

“What do you think?” I ask the girl sitting next to me in the silver hijab.

“It was good,” she says, giving an almost unnoticeable appreciative nod. Her name, she says, is Esra but she calls herself Desert Rose – even before Mazin got here Nablus’s young people had worked out how to have the rock’n’roll without the shock’n’awe.

Dr M is followed by a string of Palestinian speakers all more convincing and articulate than the Americans – despite the conference being held in English, Hosey’s mother tongue. Saed Abu Hijleh (who was shot along with his parents on the balcony of his home by Israeli soldiers during the last intifada – an attack in which his mother died) picks Hosey’s excuses apart, describing the American expansion westward as “a bloody, colonial affair”.

Mohammed Dajani from Al Quds university tells us about the Caliph Umar Al Khattab who was striving for equality for all – men, women, slaves, black, white. brown – in the Middle east, 1000 years before Hosey’s white patriarchal American ‘diversity and tolerance’ was even imagined. And Wafa Darwish tells the students “to be able to resist we have to know our enemy”. It is a pity the feisty Darwish is blind as she doesn’t get to see the CIA meatheads frantically checking the exits or the woman from the Consulate sinking lower in her seat.

When the questions roll round Hosey shuffles reluctantly back to the stand to defend his whitewashing of the great American genocide. “There are parallels in the modern world,” he acknowledges. “Like the Jews coming to colonise Israel.”

“Palestine!” comes a shout form the floor.

“Er…Sorry?” Hosey’s mouth opens and closes. This may be the last foreign assignment he volunteers for.

“Palestine,” corrects the speaker. I don’t need to look round at him, his voice carries all the rage I have no doubt is on his face. “There was no Israel before they came,” he spits. “The country they colonised was Palestine.”

Darkness descends as we slide back through Hawara and head towards the bottlenecks in the south. Above us, the hilltop settlements provoke the night with their orange glow.

“The Buddhists have a saying Salim,” says Dr M. “’Seek the low places because from there you can grow and change. But from the high places, all you can do is fall.” We all laugh, silently hoping he’s right.